Vulnerable wrecks of Lake Neuchâtel 3/3 (Switzerland, 2020)

Since Antiquity, the Swiss lakes have been central to transporting people and goods. Through the ages, many vessels were lost, some of which were buried under several meters of protective sediment. Now threatened by lake erosion, this Gallo-Roman shipwreck has recently reappeared and must be studied by scientists.

Swiss lakes are world-renowed for their rich archaeological heritage from the time of the pile dwellings, when Neolithic to Bronze Age people built their villages on the shores of alpine lakes.

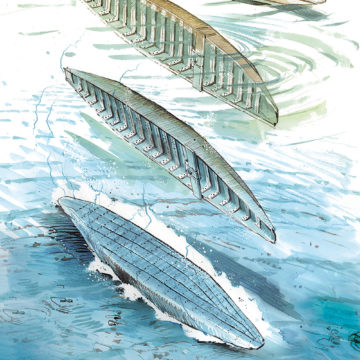

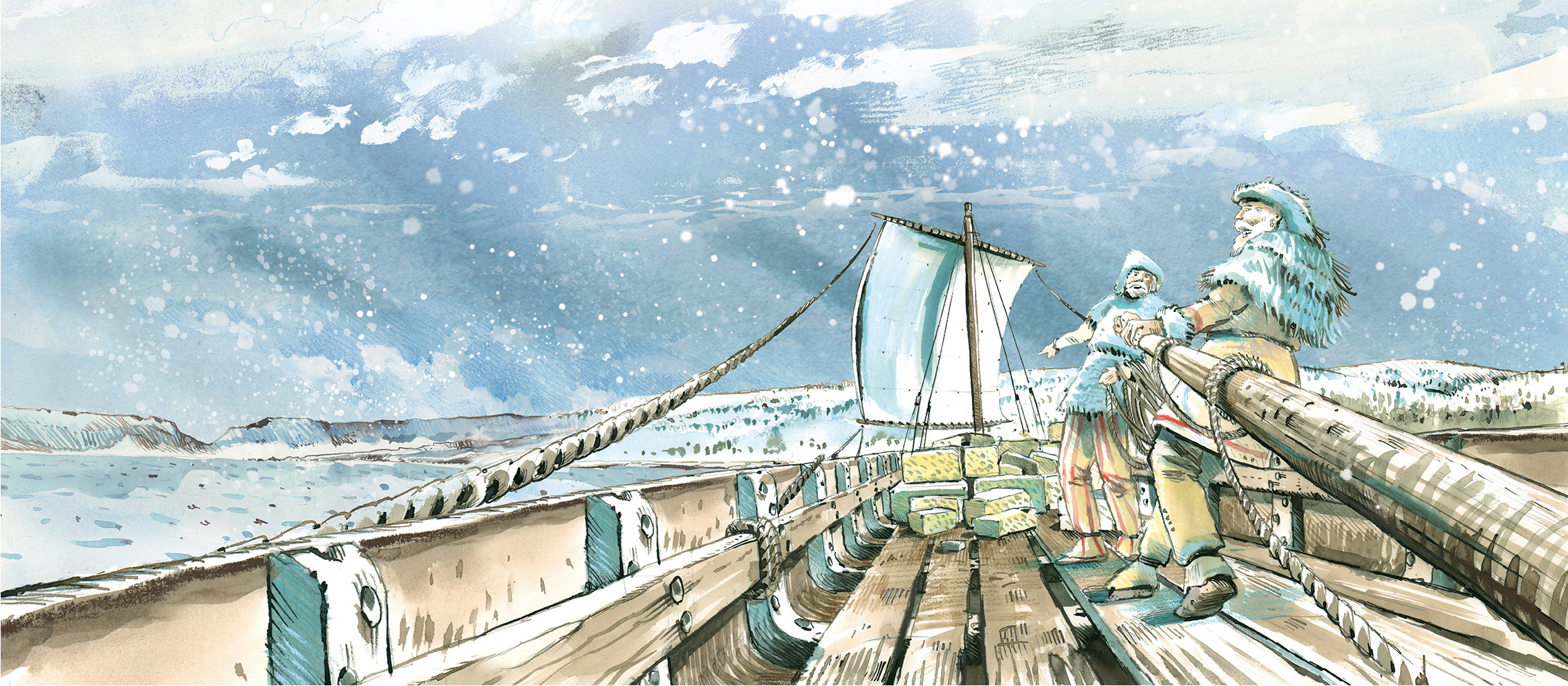

For the thousands of years that followed, people used Swiss lakes as trade routes. A precious aid for transporting goods, especially heavy or large objects. Blocks of stone extracted from the Jura quarries would have been difficult to carry on roads. Whether during the Gallo-Roman period, the Middle Ages, or the late periods, many ships did not reach their destination and sank to be quickly forgotten, buried under the sediments.

Ever changing lakes

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Three Lakes region underwent profound changes (construction of reservoirs, canals, etc.) to stabilize water levels during floods or droughts. This constraint imposed on the lakes resulted in the reshaping of their beds, much like a diverted river. This erosion primarily affects coastal areas, with significant sand shifts, bringing to light archaeological remains such as Neolithic dugout canoes and 19th-century barges. A fragile catalogue of forgotten witnesses to our history.

Our recent underwater excavation project focuses on several shipwrecks which, due to their age and state of preservation, are invaluable sources for understanding the evolution of naval architecture and navigation in the Three Lakes region of Switzerland.

These remains were discovered during aerial prospecting flights. Fabien Langenegger, archaeologist at the office of heritage and archeology of the canton of Neuchâtel (OARC), is responsible for monitoring local underwater heritage. For many years, he has collaborated with the balloonist and engineer Fabien Droz to monitor the erosion fronts that endanger the prehistoric pile dwellings, but also to prospect the 30 kilometers of coastline the canton of Neuchâtel enjoys.

Wood has a voice

An anomaly spotted in 2015 allowed the discovery of a Gallo-Roman barge that is about two thousand years old. In 2017, a pile of large stone blocks led to the discovery of a second wreck, dated precisely to 1776 thanks to dendrochronology (a scientific method allowing the dating of pieces of wood by counting and measuring the tree rings). A third wreckage, which appears to have been intentionally sunk in the 16th century for the foundation of a signal, completes this trio of outstanding vestiges.

The rare barges that have been found in our lakes have almost all sunk with their cargo of limestone blocks, creating reliefs visible from the air. These boulders also helped stabilize the remains of the wreckage by keeping it at the bottom until silted up.

High scientific stakes

To date, only three Gallo-Roman wrecks have been identified and studied in Switzerland. In addition to the one discovered in the bay of Bevaix (NE) and presented in the navigation room of the Laténium Museum, a boat and a barge were excavated in Yverdon-les-Bains (VD) visible at the Yverdon Museum.

The new shipwrecks discovered by Fabien Langenegger could prove to be historically important, as some parts of the ship (such as one of its sides) could be very well preserved.

The new shipwrecks discovered by Fabien Langenegger could prove to be historically important, as some parts of the ship (such as one of its sides) could be very well preserved.

In the region of Trois-Lacs and Léman, there is a 1700-year gap to fill, between Roman boats dating from the 2nd century AD. and the many 19th century boats that were found. The study of the remains of the 16th and 18th century boats may therefore be paramount to better understanding the evolution of shipbuilding on our lakes.

Short-term threats

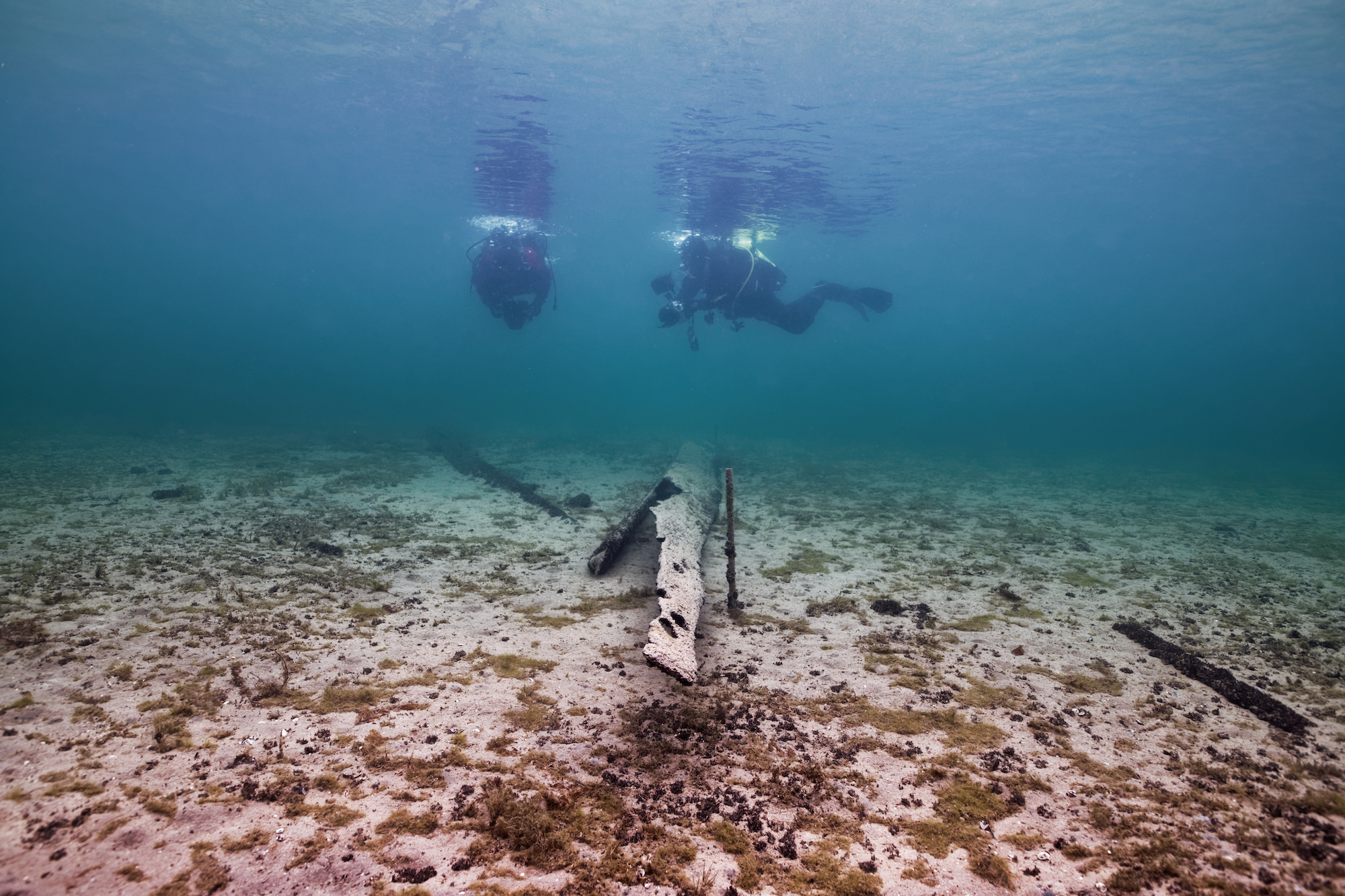

Located at a shallow depth and protected by a thin layer of sediment, the three wrecks are now vulnerable, as they are located in a part of the lake particularly exposed to prevailing winds.

For this third project to study and preserve lake heritage, the Octopus Foundation provided a team of five qualified divers and a pilot of aerial and underwater drones.

The foundation thus supports the collection of scientific data and informs the public about the objects of study. In exchange, the OARC allows the Octopus Foundation to acquire expertise in underwater archaeological excavation techniques in cold water and to publicize the excavation on its own behalf and on behalf of the OARC.

The third campaign was scheduled for March 2020, but finally took place in September 2020 due to the COVID19 crisis. It allowed for the excavation of the remains of a Gallo-Roman barge, composed of an assembly of oak planks which must have formed the side of a barge.

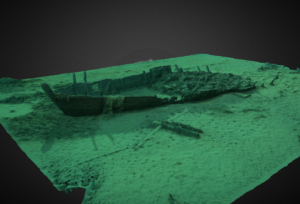

Thanks to underwater 3D modeling, the objective is to keep a record of each stage of the underwater excavations.

The Octopus Foundation was easily convinced by the idea of collaborating on inland water issues, particularly for the study and preservation of shipwrecks threatened by underwater erosion.

In November 2018, a scouting mission brought together Fabien Langenegger and the Octopus Foundation diving team to collect all the data necessary for the preparation of the project. During this short three-day mission, it was also possible to dive on the wreck of the Quai Osterwald in Neuchâtel. This ship, which sank in 1853, is 30 meters long and lies between seven and eight meters deep. In one dive, the team was able to deploy the underwater markup and make a photogrammetric acquisition of nearly 600 photos. The 3D model of this magnificent wreck is available here.

In November 2018, a scouting mission brought together Fabien Langenegger and the Octopus Foundation diving team to collect all the data necessary for the preparation of the project. During this short three-day mission, it was also possible to dive on the wreck of the Quai Osterwald in Neuchâtel. This ship, which sank in 1853, is 30 meters long and lies between seven and eight meters deep. In one dive, the team was able to deploy the underwater markup and make a photogrammetric acquisition of nearly 600 photos. The 3D model of this magnificent wreck is available here.

Aerial drones

The use of aerial drones is particularly useful for detecting underwater objects when they are at shallow depth and in clear water.

By flying several tens of meters above the surface, the pilot may spot the wrecks and pin them on a map. The drone can thus scan certain areas which will then have to be excavated by underwater archaeologists.

For this project, the use of several drones with different optics will help archaeologists collect valuable data on these wrecks.

Underwater drone (ROV)

Using the OpenRov Trident may help us to:

Using the OpenRov Trident may help us to:

– preview a wreck before sending a team of divers

– perform photogrammetry and 3D modeling of submerged sites

– capture images at depths and in areas difficult to access by diver

3D models of wrecks

Once the underwater photographic acquisition has been completed, the Octopus Foundation processes the data to obtain a 3D modeled area like the ones below.

By clicking on the symbol in the center of the window, once the model is loaded, you can rotate the area by clicking in the center and moving the cursor. You can also zoom and move the model by holding down the shift key.

These simple and free tools provided by the Octopus Foundation allow people with little or no diving experience to explore the depths of the lakes and seas, and study various archaeological pieces with no risk of damage.

Photogrammetry

Whether for the public or diving enthusiasts, these digital models are effective visualization tools. But are they also useful for scientists? We keep in mind that one of the first objectives of the Octopus Foundation is to support research and scientific exploration of the oceans.

From the digital 3D model, a simple visualization element, the computer program makes it possible to extract a scientific tool: the orthophotoplan. By a vertical projection of the entire relief on a horizontal plane, this centimeter-accurate map respects all dimensions on the ground. While diving time is limited by the air contained in a tank, it is now possible to extract the archeological site out of the water to allow it to be studied carefully on land.

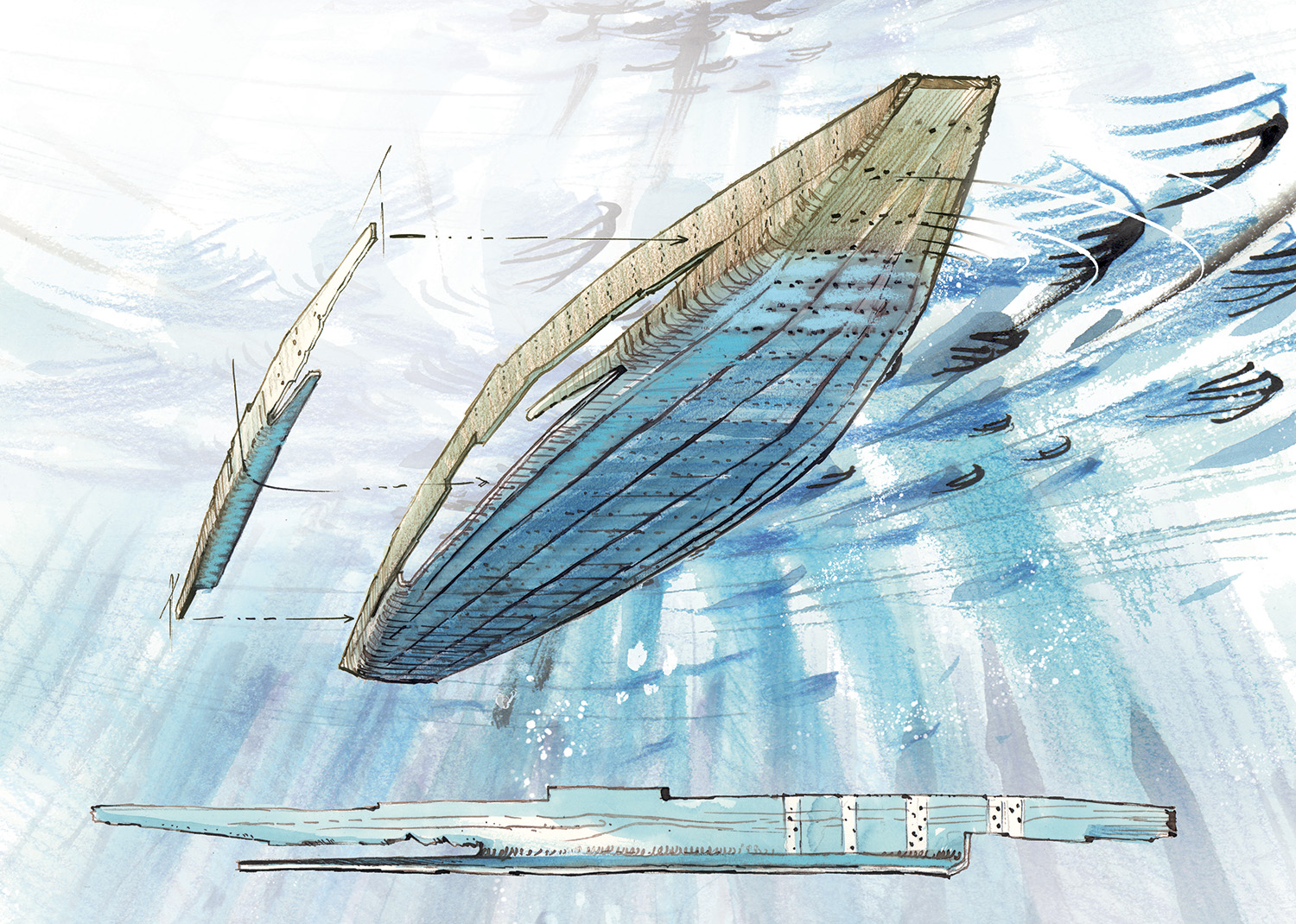

The Gallo-Roman barge

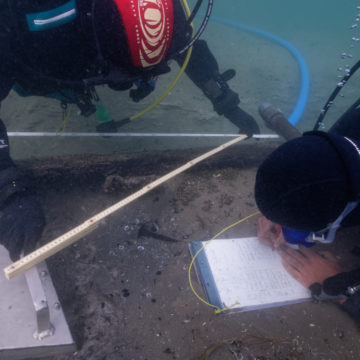

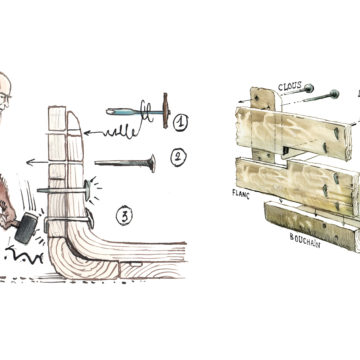

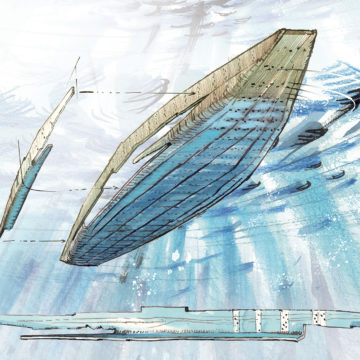

During the first dive, the identification of a Gallo-Roman barge was beyond doubt. Fabien Langenegger discovered an assembly of oak planks appearing slightly above the lake sediments and, along its entire length, a plank fixed with large forged nails on the curves (also made of oak) spaced every 80 to 90 cm.

After the first two wrecks studied in 2019 (March and October), this third field mission aimed to reveal, document and re-bury the remains of the wreck of a flat-bottomed barge, dated by dendrochronology to 121 AD, i.e. the Gallo-Roman period.

This underwater archaeological excavation mission was conducted from September 16 to October 1, 2020, with a team of four divers and a drone pilot.

This mission revealed the ten-meter-long side of an exceptionally well-preserved barge in the lacustrine chalk at a depth of approximately two meters. In the immediate vicinity of this side, the team was also able to study in detail the monoxyl chine (a large piece hewn and hollowed out with an axe from a single tree trunk) of this side. This is the key solid oak component that joins the side to the bottom of the boat’s hull. The side and the chine are rare pieces, as, until now, none of the Gallo-Roman barges found in Alpine lakes (Bevaix, Yverdon, etc.) had still their sides. This very fragile piece is systematically missing, as it is usually the first to break during the shipwreck.

During the excavations, several objects of interest were discovered, including nearly 200 forged nails (ranging in size from 5 to 20 cm in length), two flat metal reinforcement bars, and a piece of leather. These items were carefully transferred to OARC’s laboratory by Fabien Langenegger.

This study, made possible by the fieldwork of the team assembled for this mission by the Octopus Foundation, will allow the Cantonal Archaeology Office to complete the current state of knowledge on the naval architecture of our lakes in the Gallo-Roman period.

This barge has been dendrochronologically dated to 120 AD, during the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. At that time, the city of Aventicum (modern-day Avenches) on the shores of Lake Murten was a very important Gallo-Roman city, serving as the capital of Helvetia. It boasted nearly 20,000 inhabitants, a significant number in the Antiquity. Originally a small Celtic settlement, Aventicum’s destiny changed dramatically when Emperor Vespasian elevated it to the status of a Roman colony in 69 AD, under the name Colonia Pia Flavia Constans Emerita Helvetiorum Foederata. Emperor Vespasian had a particular affinity for the city, as his father and his son Titus (the future emperor) had lived there for many years. His father worked as a banker. With this new status, the city undertook monumental works, beginning with an impressive 5.5 km long and eight-meter high city wall, fortified with 70 defensive towers, protecting a territory of 230 hectares. Construction of this gigantic wall began in 72 AD and lasted about twelve years. Experts estimate that building this monumental structure required two barges like the one whose side we have discovered, each carrying 15 tons of stone blocks, to make the journey between Hauterive and Avenches every day for twelve consecutive years. It is highly likely that during this 45 km round trip, many barges encountered difficulties or even sank. This is all the more significant given that, following the construction of the city wall, a theater, a sanctuary, a forum, and a large amphitheater were also planned. These imposing public buildings also required transporting very large quantities of stone from the Jura Mountains by barge.