Vulnerable wrecks of Lake Neuchâtel 1/3 (Switzerland, 2019)

Since Antiquity, the Swiss lakes have been used to transport people and goods. Many vessels were lost through the ages, to be forgotten under several meters of protective sediment. The constant erosion of our lakes reveals new remains, that must rapidly be studied before they are forever lost.

Swiss lakes are world-renowned for their archaeological wealth from the prehistoric pile dwellings era, when people from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age built their villages on lakeside stilts.

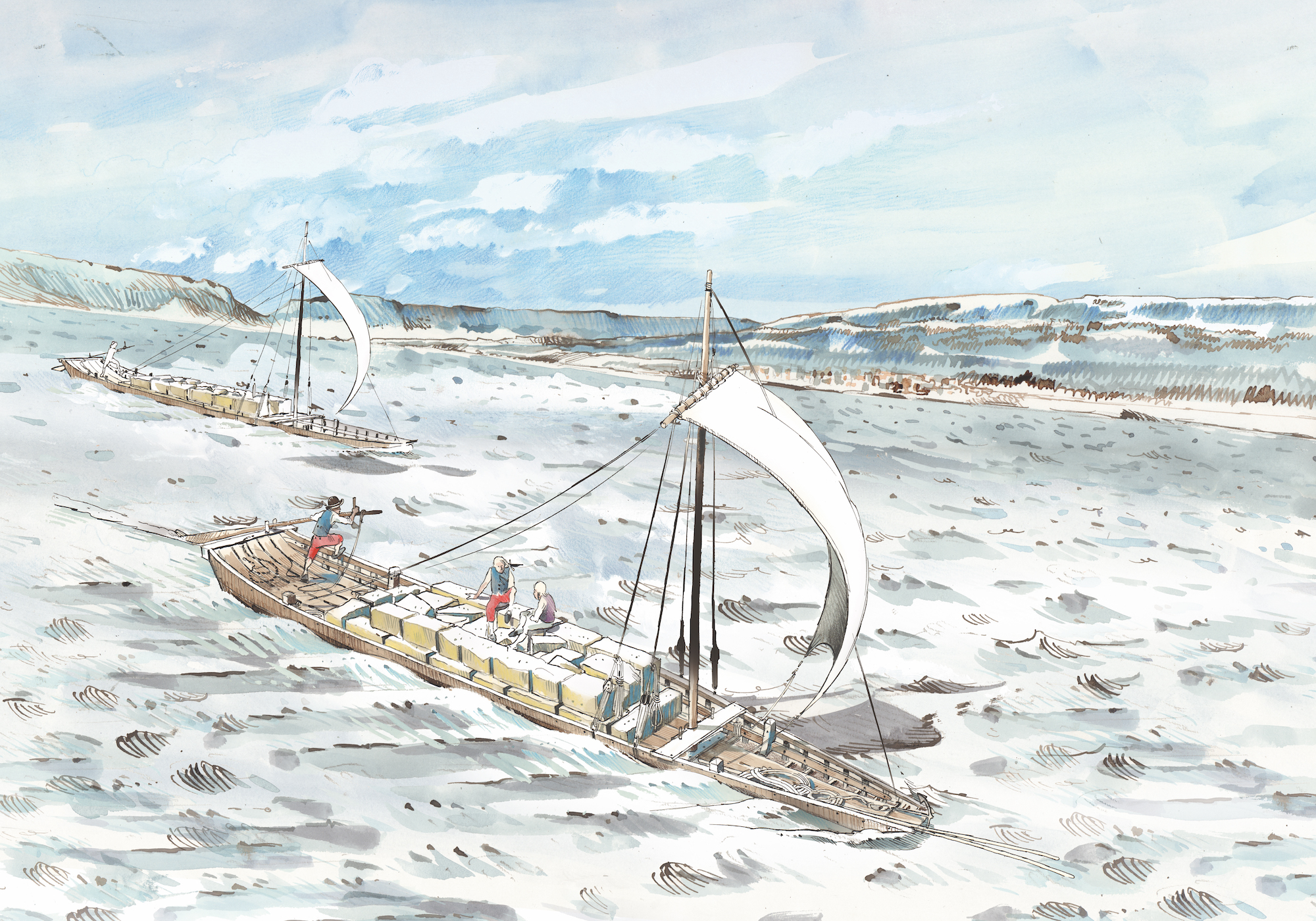

For the thousands of years that followed, people used Swiss lakes as trade routes. A precious aid for transporting goods that are too large or heavy for difficult land routes, such as blocks of stone extracted from the Jura. Whether during the Gallo-Roman period, the Middle Ages, or the late periods, many ships did not reach their destination and sank to be quickly forgotten, buried under the sediments.

Ever changing lakes

Today, the erosion of the bottom of the lakes brings back certain vestiges, from the Neolithic canoe to the 19th century barge. So many forgotten and fragile witnesses of our history. This recent underwater excavation project concerns several wrecks which, by their age and state of conservation, are invaluable testimonies for understanding the evolution of naval architecture and navigation in the Swiss region known as “Three Lake Country”.

Today, the erosion of the bottom of the lakes brings back certain vestiges, from the Neolithic canoe to the 19th century barge. So many forgotten and fragile witnesses of our history. This recent underwater excavation project concerns several wrecks which, by their age and state of conservation, are invaluable testimonies for understanding the evolution of naval architecture and navigation in the Swiss region known as “Three Lake Country”.

These remains were discovered during aerial prospecting flights. Fabien Langenegger, archaeologist at the office of heritage and archeology of the canton of Neuchâtel (OPAN), is responsible for monitoring local underwater heritage. For many years, he has collaborated with the balloonist and engineer Fabien Droz to monitor the erosion fronts that endanger the prehistoric pile dwellings, but also to prospect the 30 kilometers of coastline the canton of Neuchâtel enjoys.

Wood has a voice

An anomaly spotted in 2015 allowed the discovery of a Gallo-Roman barge that is about two thousand years old. In 2017, a heap of large blocks of stone led to the discovery of a second wreck, dated precisely to 1776 thanks to dendrochronology (a scientific method allowing the dating of pieces of wood by counting and measuring the tree rings). A third wreckage, which appears to have been intentionally sunk in the 16th century as the basis for building a signal, completes this trio of outstanding vestiges.

An anomaly spotted in 2015 allowed the discovery of a Gallo-Roman barge that is about two thousand years old. In 2017, a heap of large blocks of stone led to the discovery of a second wreck, dated precisely to 1776 thanks to dendrochronology (a scientific method allowing the dating of pieces of wood by counting and measuring the tree rings). A third wreckage, which appears to have been intentionally sunk in the 16th century as the basis for building a signal, completes this trio of outstanding vestiges.

The rare barges that have been found in our lakes have almost all sunk with their cargo of limestone blocks, creating reliefs visible from the air. These boulders also helped stabilize the remains of the wreckage by keeping it at the bottom until it was silted up.

High scientific stakes

To date, only three Gallo-Roman wrecks have been identified and studied in Switzerland. In addition to the one discovered in the bay of Bevaix (NE) and presented in the navigation room of the Laténium Museum, a boat and a barge were excavated in Yverdon-les-Bains (VD) visible at the Yverdon Museum.

The “new” Gallo-Roman wreck discovered by Fabien Langenegger could prove to be historically important, as certain parts of the ship (such as one of its sides) could be very well preserved.

The “new” Gallo-Roman wreck discovered by Fabien Langenegger could prove to be historically important, as certain parts of the ship (such as one of its sides) could be very well preserved.

In the region of Trois-Lacs and Léman, there is a 1700-year gap to fill, between Roman boats dating from the 2nd century AD. and the many 19th century boats that were found. The study of the remains of the 16th and 18th century boats may therefore be paramount to better understanding the evolution of shipbuilding on our lakes.

Short-term threats

Located at a shallow depth and protected by a thin layer of sediment, the three wrecks are now vulnerable, as they are located in a part of the lake particularly exposed to the prevailing winds.

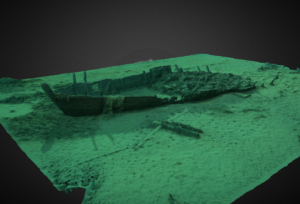

For this first lake heritage preservation project, the Octopus Foundation will provide a team made up of five qualified divers and two aerial and submarine drone pilots. This field team will assist the archaeologists in their excavation project. Thanks to underwater 3D models, the objective is to keep track of each step of the underwater excavations.

The Octopus Foundation was thrilled to be able to work almost “at home”, in particular for the study and preservation of wrecks threatened by underwater erosion.

The Octopus Foundation was thrilled to be able to work almost “at home”, in particular for the study and preservation of wrecks threatened by underwater erosion.

In November 2018, a scouting mission brought together Fabien Langenegger and the Octopus Foundation diving team to collect all the data necessary for the preparation of the project. During this short three-day mission, it was also possible to dive on the wreck of the Quai Osterwald in Neuchâtel. This ship, which sank in 1853, is 30 meters long and lies between seven and eight meters deep. In one dive, the team was able to deploy the underwater markup and make a photogrammetric acquisition of nearly 600 photos. The 3D model of this magnificent wreck is available here.

In November 2018, a scouting mission brought together Fabien Langenegger and the Octopus Foundation diving team to collect all the data necessary for the preparation of the project. During this short three-day mission, it was also possible to dive on the wreck of the Quai Osterwald in Neuchâtel. This ship, which sank in 1853, is 30 meters long and lies between seven and eight meters deep. In one dive, the team was able to deploy the underwater markup and make a photogrammetric acquisition of nearly 600 photos. The 3D model of this magnificent wreck is available here.

Aerial drones

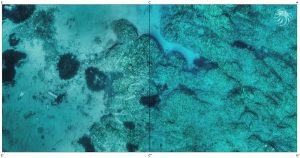

The use of aerial drones is particularly useful for detecting underwater objects when they are at shallow depth and in clear water.

By flying several tens of meters above the surface, the pilot may spot the wrecks and pin them on a map. The drone can thus scan certain areas which will then have to be excavated by the underwater archaeologists.

For this project, the use of several drones with different optics will help archaeologists collect valuable data on these wrecks.

Underwater drone (ROV)

Using the OpenRov Trident may help us to:

Using the OpenRov Trident may help us to:

– preview a wreck before sending a team of divers

– perform photogrammetry and 3D modeling of submerged sites

– capture images at depths and in areas difficult to access by divers

3D models of wrecks

Once the underwater photographic acquisition has been completed, the Octopus Foundation processes the data to obtain a 3D modeled area like the ones below.

By clicking on the symbol in the center of the window, once the model is loaded, you can rotate the area by clicking in the center and moving the cursor. You can also zoom and move the model by holding down the shift key.

These simple and free tools provided by the Octopus Foundation allow people with little or no diving experience to explore the depths of the lakes and seas, and study various archaeological pieces with no risk of damage.

Photogrammetry

Whether for the public or diving enthusiasts, these digital models are effective visualization tools. But are they also useful for scientists? We keep in mind that one of the first objectives of the Octopus Foundation is to support research and scientific exploration of the oceans.

From the digital 3D model, a simple visualization element, the computer program makes it possible to extract a scientific tool: the orthophotoplan. By a vertical projection of the entire relief on a horizontal plane, this centimeter-accurate map respects all dimensions on the ground. While diving time is limited by the air contained in a tank, it is now possible to extract the archeological site out of the water to allow it to be studied carefully on land.